Hyperallegic talked to Sheida Soleimani about her life as a wildlife rehabilitator, artist and professor.

Read the full article by Sarah Rose Sharp here

Inside the Life of Bird-Rehabilitator-Artist-Professor Sheida Soleimani

The artist’s work is the cognitive equivalent of a rock-climbing wall, in which visual handholds open up interpretive pathways.

To hear Iranian-American artist, educator, and wildlife rehabilitator Sheida Soleimani tell it, there was a time when she worked hard to compartmentalize her various occupations and personas.

“I have had three different kinds of working identities at any given point, and for a really long time I kept those separate,” Soleimani told Hyperallergic in an interview. “It was like Sheida-the-artist makes work that politically engages with the greater SWANA region, and Sheida-the-bird-rehabber does wildlife work, and then Sheida-the-professor teaches about art and activism. It was getting to the point where I asked myself: Why am I working so hard to keep all of these identities separate? I think part of being an artist is having a kind of weird, blended life, and allowing things to collapse in on each other.”

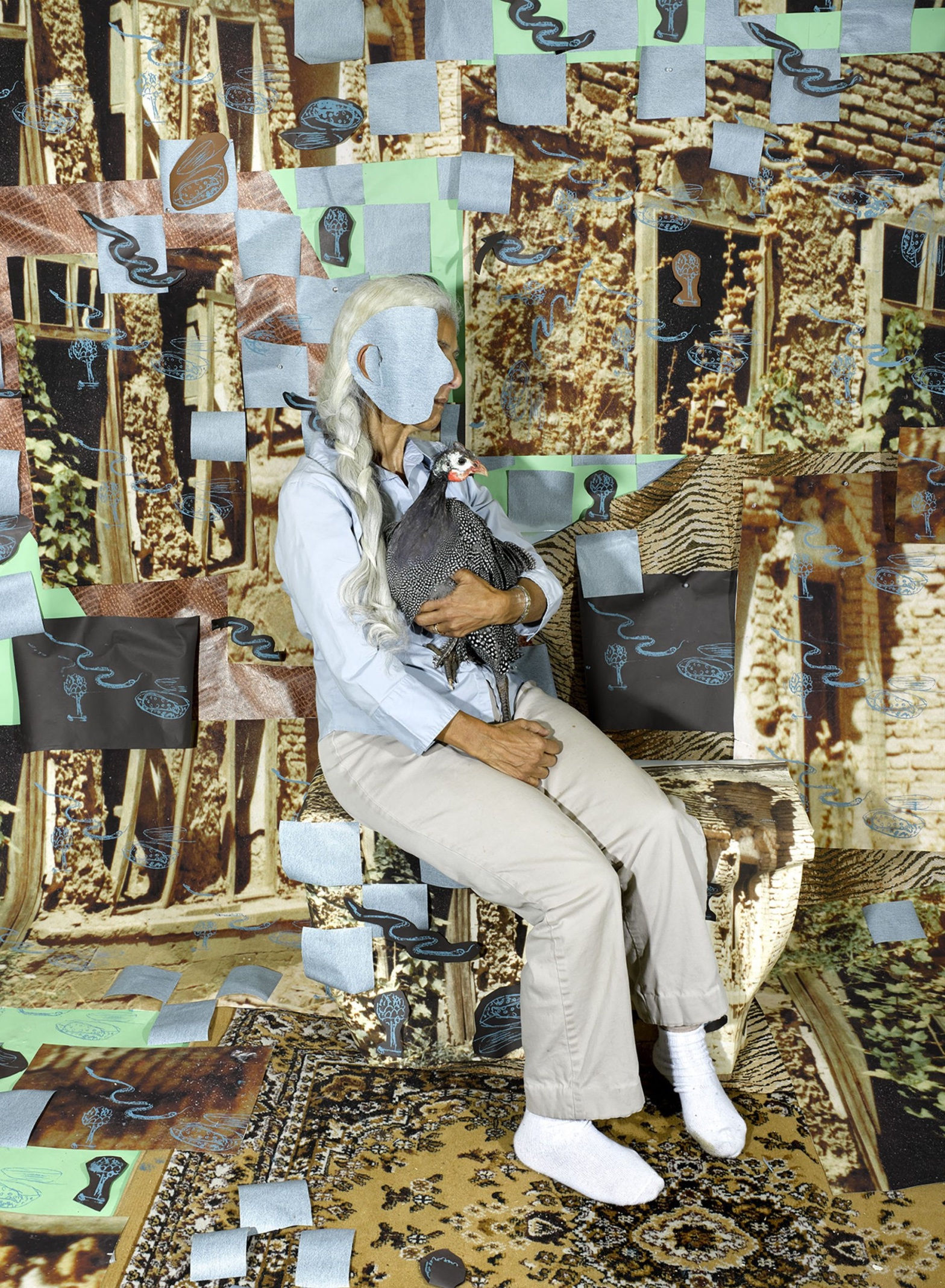

Sheida Soleimani, Noon-o-namek (bread and salt), 2021, Archival pigment print, 62 x 45 5/8 in

Case in point, during the interview, which took place over Zoom, a pair of parakeets flew over to perch upon Soleimani. The duo recently crossed over from her avian rehab facility, Congress of Birds, into the menagerie of personal pets that live in her home.

“Someone dropped them off on the doorstep in a bag that said ‘Happy Birthday’ on it, and they were teeny-tiny,” Soleimani said, a juvenile yellow parakeet roosted inquisitively on her shoulder. “It was the middle of winter, a weird time of year for baby birds. So I got in touch with a parrot sanctuary, and they were happy to take them, but not until I hand-fed them enough to get them eating on their own.”

Soleimani found herself charmed by the sociability of the parakeets, and made them a permanent part of her home.

“They’re a bird version of a lap dog,” she laughed.

Soleimani learned the practice of bird rehabilitation from her mother, part of a cultural inheritance that also included deep trauma. In Iran, her pro-democracy parents were incarcerated; they eventually escaped and resettled in the United States. Earlier bodies of work, such as 2018’s 'Medium of Exhange' and 2020’s 'Levers of Power', have dealt with the international politics and oil commoditization of Iran and the surrounding region in a broader way.

Her most recent photographic series, 'Ghostwriter' (2021–23), takes a much more personal tack. Not only are the stories close to Soleimani’s heart and family, but they are living stories, in a literal sense — she employs the birds and her own parents as subjects. With a unique style that bridges photography, installation, and collage, Soleimani creates densely symbolic and textured tableaux that demonstrate the synthesis between the worlds that Soleimani struggled for a time to keep separate.

Portrait of Sheida Soleimani, 2022. Photo by Eugene Gologursky/Getty Images for WomanLifeFreedom.today

“I think a lot about being of the Diaspora, being an immigrant, and what it means to have a home,” said Soleimani. “I think home is actually just a collage of a bunch of different things, and collage is also really important in my practice.” In layering and building her images, Soleimani contemplates ways in which we assign hierarchy based on perception of the subject — including whether it is living or animate — and whether that hierarchy can be flattened.

“I’m thinking about living materiality versus that which is very much constructed and fake,” she said. “I’m not interested in hierarchy being built between characters; I’m interested in collaging them into this kind of weird, diasporic stand-in for home.”

Soleimani’s tableaux involve layers upon layers of visual synecdoche. The mountains through which her father made his escape on foot from Iran become a few rocks, villages are reduced to single structures, and landscapes are shattered into a mosaic of repeating parts. The images are governed by a dreamlike logic, laden with symbolic significance. Soleimani’s consideration of her elements verges on the obsessive: She often pulls from an “object library” that includes crab pots, dried vegetation, chairs, mirrors, and much more, which lives and grows in her studio. The visually chaotic interplay that results demonstrates trust in the viewer to navigate toward their own conclusions. Parsing Soleimani’s imagery is the cognitive equivalent of a rock-climbing wall: It has numerous visual handholds, any of which can open a pathway through the work.

A work in progress in Sheida Soleimani's studio, 2024

The 'Ghostwriter' works are, in Soleimani’s words, “a space where these elements all get to collide and live amongst one another.”

This increasing synthesis between Sheida-the-artist and Sheida-the-bird-rehabber has also spread to include her third realm: that of Sheida-the-professor.

“I love teaching,” she said. “I mean, I love a sabbatical, don’t get me wrong, but I’m not the type of artist that is in the studio every day. It took a sabbatical for me to realize that there’s actually so much that I get from being in the classroom with my students. I see so many people refusing to adapt or be in touch with what’s happening with individuals that are younger than us, and I think teaching is such an important way of doing that. I need to continuously be refashioning my ideologies and thinking about how I interact with the world.”

For Soleimani, teaching is an indispensable part of her process, even when the demands of a teaching schedule fight for her time and energy in the studio.

“So many people get comfortable with what they know or how they’ve lived something or experienced something, and that sets the tone for the rest of their lives,” she said. “I see teaching as being a form of updating my own syllabus for my practice and artwork.”

Sheida Soleimani, Recall, 2023, Archival pigment print, 40 x 30 in