-

-

Roaming in Bomber Jackets

Text by Ive Stevenheydens“Don’t blame the sweet and tender hooligan, hooligan Because he’ll never, never, never, never Never, never do it again, not until the next time.”

- The Smiths, Sweet and Tender Hooligan

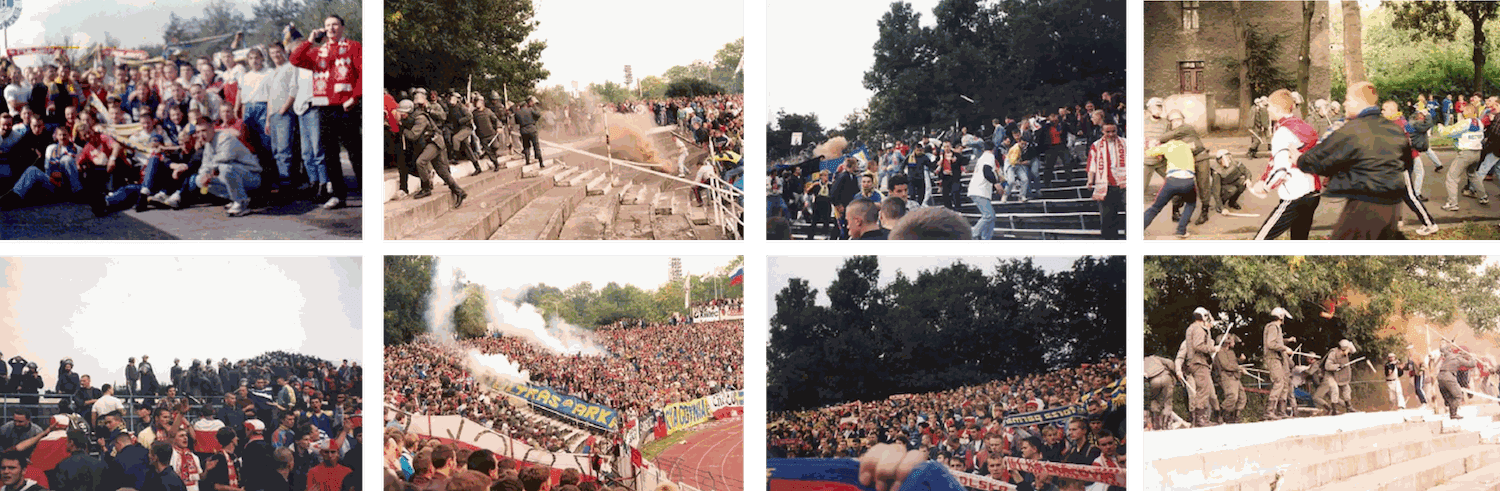

Cracow, Wednesday 24 April 1996. The air in the city feels fresh: even after six years, it still tastes of liberation. While the whole country is groaning under poverty, it is in a strange state of excitement, that of complete transformation. Poland is in transition: from communism to capitalism. Marcin Dudek is also in transition. Yet this young man has a lot behind him. Sweet sixteen, but far from immaculate. Wednesday 24 April 1996, in the centre of Cracow. Marcin is meeting mates at the Plac Bohaterów Getta, their usual gathering spot in the city. With its austere, squat terraced houses from the 1930s and its newly constructed but just as compact glass office tower, it's a nondescript place. But still, it's a popular haunt. Convenient: close to the river, away from the hustle and bustle of the city centre, and - especially for these guys - boasting a direct tramline to the football stadium. Marcin's 'team' congregates on the square. Cigarettes, beer and vodka. Bomber jackets, sweatpants, Adidases, red-and-white scarves. One of Marcin's pals shoves a gram of speed into the zippered pocket of his left-hand sleeve, which is the perfect size for a packet of cigarettes and his stiletto. The back of Marcin's bomber jacket is spray-painted with "KS", the initials of the football team Cracovia: these guys are its diehard supporters. The tram arrives. When the doors creak shut, all three grab their cigarettes between thumb and forefinger and flick the butts into the gutter.

Wednesday, 24 April 1996. At 5 p.m. today, in their very own stadium, KS Cracovia is playing a home match against Stalowa Wola (a club named after a city five hours to the east). Inaugurated in 1912 with a match between Cracovia and Pogoń Lwów, the stadium has changed radically in recent decades. Floods, aerial bombardment during the Second World War, storms and a huge fire in the 1960s prompted several reconstructions. Several facade renovations have culminated in the concrete mishmash of the site today, a veritable architectural jumble.

For Marcin and his mates, it’s home. They’re proud of their team but also of their stadium. Whenever they enter the car park through the half-rusted fence, their hearts quicken. Especially at a match like today’s. Behind the twelve-metre high concrete back of the stands, cheering and singing can be heard. Some of the smoke drifts across the corrugated roof. Orange, tinged with grey and white. After their short trek through the dark and dank corridor (as chilly in summer as it is in winter), there lies the pitch. On the stands, the white-and-red Cracovia flags contrast with the green-and-black colours of the rival fans. Above them, in the centre, are the scoreboards. These too have had their day. They regularly fail. 0:0 they declare. And then go dark.

It was a close call: the police approved the match with only half an hour to spare. Too risky, too explosive a crowd in the stands. On the pitch, both teams attack. But there are few real chances to score a goal. It’s what you’d call a boring game. Does it matter? Marcin and his mates follow the action but are easily distracted. For now, there’s still enough vodka and speed to get them through. At the 16th minute, the host team misses a devilish opportunity: goalkeeper Kwedyczenko catches the ball. A swell in the stands.

And then suddenly, a scream, a signal from Marcin’s mates. They turn their bomber jackets inside out. In the stadium, here and there, other groups follow. The black exteriors suddenly turn a vivid orange. They chant and sing, they shout until their smokers’ lungs hurt and they start to cough. Marcin loves the adrenaline. Jacket inside out, he steps into another realm, as though entering a forbidden land. It’s a victory, like breaking a non-existent law. For him, it’s an almost mystical experience. Now he genuinely feels part of the surrounding masses. The mental shift is liberating. Marcin detaches himself from his identity and lets himself to be subsumed by the group. A whistle. It’s still 0:0. The stands explode. Orange smoke obliterates the view. Now the real game begins. Outside the stadium, life, danger and confrontation await. This is where the daily fight will be found.

Laeken, 22 March 2021. Today, Marcin Dudek has completely distanced himself from past as a football hooligan. Completely? Actually, not at all. Although he is no longer actively involved in such circles – rest assured, he’s one of the gentlest people you could ever wish to meet – his artistic practice has revolved around his former life in Poland since 2013. Profoundly autobiographical ideas in his work form a digestive engine that enables him to process these past experiences. It allows him to control his emotions on a daily basis. Ask him yourself: his work may be somewhat therapeutic, he thinks. But he also sees this as one of the great strengths of art in general. In his output, Dudek reveals his emotions. Using DIY strategies, he translates his feelings into objects, collages, videos, performances and more, in which the rituals of the subculture and the violence of the masses are transformed into universal stories. These are struggles that are frighteningly readable to everyone.

-

The installation/sculpture/environment Passage (2021), seven metres high and twenty metres long, is his most ambitious work to date. It transports us from A to B, inviting us to embark on a physical journey. In addition, it forms a bridge, a transition between an oppressive state of mind and a more purifying one. Made from some 300 individual bomber jackets, this immense garment asserts itself as a single entity. As though it's a group of people who have decided to henceforth function as one body. (1) The bomber jackets that today form Passage first started to appear in Poland from the 1990s onwards, all surplus to requirements in the West. Dudek sourced some 300 models from second-hand shops. This hand-picked neglect of the West mainly came from the UK, Scandinavia and the Benelux. With its shipment to Brussels in early 2021, some of these coats returned home (an interesting swing of the pendulum that could be placed in an economic template, but that's taking it a bit too far). In the workshops of "NJØRD Sew for Life" a handful of new Belgians (undocumented migrants, refugees and other people in need) diligently unpicked hundreds of bomber jackets for weeks on end. Only to immediately reassemble them into Dudek's installation.

Passage is effectively composed, therefore, of distinct but similar parts: some 300 cloth torsos comprise the new body of this giant coat, six hundred sleeve sections now make up the new, enormous arms. The work literally forms a passage: we, the viewers, enter the tunnel of the left sleeve via its cuff. Once inside, we are immersed in an alienating and resonant experience as the space reverberates with an eerie silence within the belly of 300 bodies. After a short ascent, we arrive a top a papier-mâché amphitheatre facing three intricate mixed-media paintings, which are described in further detail in Amanda Sarroff's essay "A Mantle of Flames: Marcin Dudek's Passage Series".

-

This triptych alludes to the shape of the stadium (we, the viewers, are on the pitch) and is a nod to the classic works by Bouts or Van Eyck. This formal reference is for a reason. After all, Dudek began by copying the old masters he discovered in Wielcy Malarze (a weekly collectible art magazine that slowly grew into an ‘art book’) while still an out-and-out hooligan. For Dudek, Wielcy Malarze was a never-ending collection. Every week, a different painter, each assigned a number: Dürer, Da Vinci, Tintoretto, Bouts, Bruegel... Every week was an eye-opener for Dudek – sometimes the flame would burn with unprecedented ferocity. Wielcy Malarze, his ‘second’ weekly rendezvous, gradually transformed into his new football club. Again: art as therapy? The artist sees it more as a form of escapism, powerfully fed by the cliché – fascinating nonetheless – of the bon vivant artist. Moreover, the horizons in the old master paintings had Dudek in their grip. He felt the paintings were also infinite, always offering new possibilities. Art effectively offered him an escape route of his own, a way to be independent. It was art that enabled him to break free from the toxic environment of his childhood and adolescence. In 1997, it took him to Salzburg, where his sister was studying. To this day, Dudek speaks about art school as a rebirth. A purification, a different life with new people and a fresh attitude. A year zero. Dudek emerged as a completely new person. He had found a new horizon.

-

-

Hooliganism functions like a sect, like a mafia. The leader adopts a member and instrumentalises him to commit wrongdoing. The newcomer is expected to assimilate, to behave like the others. He is supposed to copy and outdo the 'in crowd', the followers of the group; he is supposed to amaze the members with (feigned) courage and daring. The key to holding office is to break the law, preferably in a violent way. After his rites of passage, Dudek entered the circle. There, too, violence, drinking, ingesting and sniffing determined his status - daily. He skipped school and earned money, but only for the group. Nevertheless, Dudek felt relatively good. He was finally part of something bigger. With his group of twelve or thirteen mates, he travelled around Poland. They journeyed from match to match. Fighting and stealing. Paralytic and/or stoned out of their minds. In 1997, things went badly wrong. His best friend was murdered by supporters of a rival club. Dudek was given a suspended sentence in court.

-

-

-

Wearing the jacket inside out is a well-known signal in hooligan subcultures. Orange, the colour of the lining, is also often found in Dudek's work. Bearing in mind the Cooper Colours (3), orange equals a state of emergency: the moment at which one is poised to act. Or to do something insurmountable: for the hooligans, turning the bomber jacket inside out is a clear signal, both to each other and to the authorities. At that moment, the violent mass is ready to roar. Whoever turns his jacket inside out in the stadium is signalling that he belongs to a certain group but, in so doing, immediately becomes a target. Above all else, it is a warning to the outsider that the group can muster, will melt into a single entity, a multi-headed hydra that is not instinctively benevolent towards the 'others', the outsiders.

Wednesday, 24 April 1996. End of the match. Outside the stadium, the daily fight is brewing. Surging, pushing and pulling in the stadium's icy tunnel. Marcin ducks and dives to the car park. Police in armour with batons. Smoke, the chanting Stalowa Wola supporters. He has lost his mates. He is reeling from the speed and vodka. And then a scream, a thump on his shoulders and a blow to the head. Blood and concrete. White, a beeping sound, and a momentary sense of calm regained.

-

cccc

-

Conversation between Amanda Sarroff and Marcin Dudek

Marcin Dudek: Harlan Levey Projects | Slash & Burn II

Past viewing_room