Art as a strategy for living; Marcin Dudek’s practice builds from autobiographical experience and expands to explore the broader phenomenon that shaped it. These include the rituals of subculture, DIY economy and crowd violence. From 2013 to present, his work has centered around sport, spectacle and stadiums, with performances acting as vessels that allow the artist to reconnect with a past he consciously left behind. As Eddie Frankel wrote in Time Out London:

Toxic masculinity is a big topic in art, and Dudek’s work is a confrontation of it from within. This is someone who has experienced violence, has perpetrated it, lived it – this isn’t some vague, distanced, societal analysis. This isn’t an academic takedown of some faraway physical concept; this is the reality of male violence. If it feels scary, uncomfortable and wrong, that’s because it is, and Dudek knows that better than most.

On this page, Marcin Dudek answers questions about the role of performance in his practice. At the bottom of the page the entirety of the artist's performances can be viewed.

-

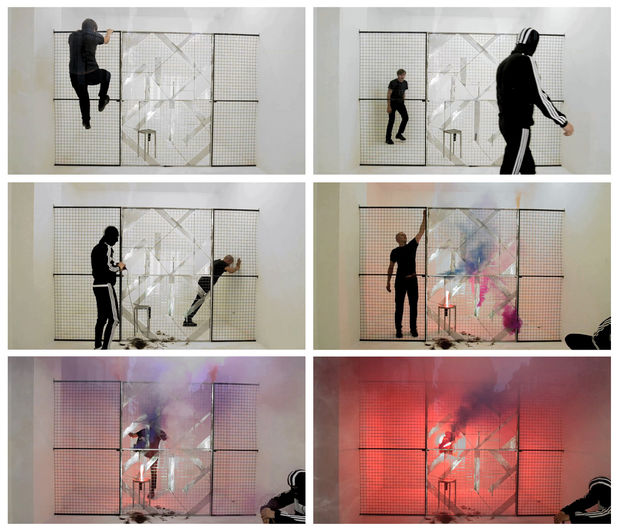

Wild, Do Not Open Project Space, Brussels, Belgium, 2013

In 2013 I changed the focus of my work, which became very personal and autobiographical. This new subject became a new territory, which is why in my first performance, Wild, I started by jumping over a fence. This was a metaphor for crossing the border into the unknown. Performance became necessary as it is the most direct and emotionally relevant medium to communicate the violence and intensity of my memories, and it is essential in order to awaken aspects of my past self through a performative transformation. The static aspect of art can be very frustrating with a past like mine, because the finished element of it can appear as an artifice. Art is a very individual, self-oriented practice, in that it helps you find your own way. When I challenge this solitary aspect with the larger themes in my practice of belonging and group psychology, it confronts and contradicts this lonely aspect of being an artist. Performance becomes the most direct way of provoking disorder.

-

The Protectionist Reflex, Poland, 2017

When I shave my head or when I put on certain clothes, such as a bomber jacket, I reveal who I used to be. This allows me to find a balance between these two personalities. I can confront my past and acknowledge that this person is still inside of me. When I relive these memories, I see that there is a bond that I cannot erase. Through performance, I can tap into this thing inside of me in a rationalised and staged way, recalling the authentic emotions that I felt and awakening signs of my past self. The experience of being in a crowd is so intense that, through performance, I can recreate its dynamics through a singular body.

-

Head in the Sand, Leto Gallery, Warsaw, Poland, 2015

When you act in an organized group, you have a specific role. It’s almost like a paramilitary group with specific logistics involved. My performances also have a structural planning, in which I create the scenography and the obstacles.

In Head in the Sand (2015), I recreated the room where I lived for almost twenty years in a housing estate in Poland. The rooms in these estates were so small, and the neighbours were so close, that it became a claustrophobic space where you felt as though you were suffocating. As much as my life outside of this room was chaotic, this space is where I first started to paint. It was a place in which I could hide from everything else, using it as a therapeutic way to transform myself. Head in the Sand refers to the idea of hiding, and for me art was the sand in which I could stick my head. I made my transformation towards an artist in this room, and during this performance I transformed from my current self as an artist to my past, aggressive, self. The room became a provocation and a means of escalating the violence I once experienced and contributed to. Just as my situation at the time pushed me to escape and become an artist, the smoke grenade in the performance suffocated me and forced me to create conditions in which I had to escape. When you stay too long in this sort of therapeutic moment, in either situation, it becomes like a prison.

-

Archival Images (1997) and Saved by an Unseen Crack, 2015

Walking through my home town, certain areas can evoke memories in which I was hurt or where I did things that injured others. By turning these recollections into art and by finding ways to express them creatively, I can deal with them. Normalising the memories of my past is a way of confronting them. When they are put into the light, they can become an accepted part of my own history instead of being monstrosities that are hidden away. Memories are impossible to get rid of, so this is my way of utilizing them. These negative energies can then be directed into a creative force. The violence, the smoke, the demolition... everything becomes a mirror of an autobiographical transition.

-

The Crowd Man, Muzeum Współczesne Wrocław, Poland, Photograph by Małgorzata Kujda, 2019

When I use smoke in my performances, it is like I am acting as a painter, using the medium of the subculture to communicate with the audience. The movement of smoke becomes a choreography, communicating emotions through colour and motion. For the piece The Protectionist Reflex (2017), I used black smoke rather than coloured smoke, which is much more aesthetic. When we see black smoke, we immediately think of fire and destruction. This work is important to me because it took place outside of the protected zone of the art world. I was directly confronting authority, in an environment which is totally unpredictable. When nobody knows what you are doing there is an ambiguity about your intentions. In this work, the audience was unclear. In this context, disorder is provoked in a very direct way. The performance was supposed to last three to four minutes, but I was stopped by the police, who fined me and held me for a few hours. The external world shut down the event before it reached its planned finale. This proved that in any performance, if you set something on fire or if you throw a smoke grenade, no matter what scale you are working on, you are confronting authority and you risk facing the consequences.

-

Tribunalia, Launch Pad Residency, Charente, France, 2018

Tribunalia was a complete 180 in regards to my previous performances, and I took on my struggle with my past in a very different way. This was the first time that I spoke, dialoguing openly between my past self and the present moment. It was a very emotional moment in which I felt the weight of the past and of this old identity. Before performing, I watched archival footage of myself participating in matches, and it directly awoke these feelings. By shifting the focus away from the uniform and from bodily props, I was able to manifest the pure energy of the moment. As the body became minimalised, the emotions are channeled through the energy stored in the arena, which becomes an extension of the self.

-

-

-