-

-

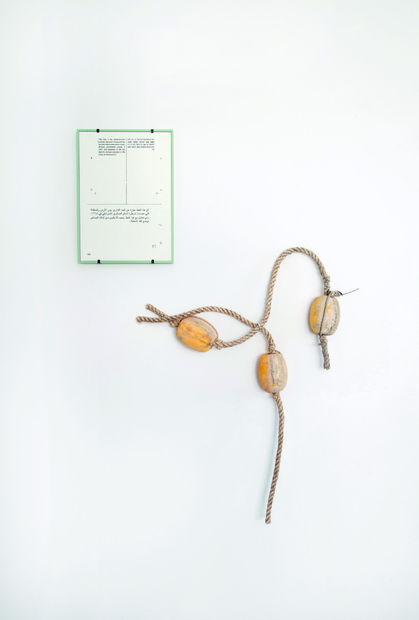

The body of work comprising "A High Degree of Certainty" - Littwitz's solo exhibition at the Center - was developed during frequent research trips to the Jordan-Israel border, on the southern part of the Jordan River, located on the colliding rift of two tectonic plates. The main site of such trips was Qasr al-Yahud, which is believed to be where the Israelites crossed the Jordan River into the land of Canaan after 40 years of wandering. According to the Christian tradition, it is also the place where St. John baptized Jesus Christ. After the 1967 occupation, due to the many infiltrations and chases that took place in it, this area was closed by the military and consequently mined. Littwitz's interest in this specific stretch of land stems from its being a cross-path of religions, geography and politics - as well as of water, soil and sky. It is a landscape that defines itself in terms of mythologies and beliefs through momentous transitions. Her works echo the Biblical and modern narratives associated with this area, presenting us with diverse examples of transition, transfiguration and the formation of political constructs through acts of belief. By bronze casting ephemeral plants and lumps of soil, Littwitz comments on the improbability of fixing concepts and truisms both into natural phenomenon and cultural constructs; by removing symbolic objects associated with this locus, the artist highlights the specific cultural and political values these very object have gained, stressing the difference between a "concept" and the object that embodies it, thus questioning precisely the sovereignty of those same concepts. In Littwitz's cosmos, the field of action is defined by the artistic objects that are presented to us as much as by the lack of their presence in their sites. Trail stones, tin triangles that indicated minefields, floaters that once marked the border between Jordan and Israel, barrels that delineated military firing ranges, and books that once had a place on people's bookshelves, are elements that trigger recollection of personal and collective memories. Through these memories, the artist reaches core concepts of belief and submission we have all internalized in order to inspect and question them. Once something is removed, there is a gap left; where there is a border or a fence, there is always the "other side"; where there is a marked path, there is also an unmarked and impassable road. The empty bookshelves, the unmarked paths and the removed borders and limits are in fact the alternative. Facts on the ground are useless, there is no degree of certainty, only systems of belief, as in art itself.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

A High Degree of Certainty: SOLO EXHIBITION: ELLA LITTWITZ AT THE CENTER FOR CONTEMPORARY ART, TEL AVIV. CURATED BY SERGIO EDELZSTEIN

Past viewing_room